Talking about a city’s infrastructure is normally as interesting as watching paint dry. Unless, of course, you live in a city like Calgary these days. That’s because this seemingly modern city in one of Canada’s most prosperous provinces has declared a state of emergency over its water supply.

There is a credible risk that the city will run out of the ability to deliver water to its 1.6 million citizens over the next four or five weeks – the latest estimate of how long it will take to repair several weak spots in the largest watermain the city has. After reacting with a collective shrug to the initial word of the break, most citizens are showing growing alarm and getting serious about both cutting back water use and ratting out scofflaw neighbours who want to keep watering their lawns and washing their cars.

Pundits are now referring to this as the biggest crisis the city has faced since the 2013 floods that devastated downtown neighbourhoods and – heaven forbid! – threatened to sink that year’s Calgary Stampede. In the end, Herculean efforts by volunteers and paid staff meant the show could go on. Will this year be a dry Stampede? Not as long as we have Coors Lite.

It’s early to start playing the blame game (Mayor Jyoti Gondek tried blaming the province until Premier Danielle Smith smacked her down), but city dwellers surely have a right to wonder how a city with a modern works department and modern technology couldn’t foresee this catastrophic failure coming. Why did we wake up one morning to find a major road flooded out and an entire west-end neighbourhood waterless?

The city was blasted for doing a terrible job communicating the problem. It has now posted a , claiming that pipes like the one that ruptured can last as long as 100 years “in ideal conditions.” This watermain was installed in 1975, making it 49 years old.

The city states that some maintenance work was done this spring, including replacing air valves and installing an acoustic monitoring device (which is supposed to detect leaks). It goes on to say a full condition assessment was planned for December 2024. Oops.

Sound a bit defensive to you? It does to me. I am also not reassured by the city’s claim that 98 percent of Calgary’s feeder mains “are in good or very good condition.” If that were true, then citizens shouldn’t feel they had to rush off to Costco to stock up on bottled water, would they?

No, much as I hate to kick a dead horse, I can’t help but feel that, one day, we will learn that persons on the city payroll were asleep at the switch. Or that contractors hired to do the work cut some corners.

If you want to know what’s really going on with your city’s infrastructure, you could do worse than refer to the , a national survey of the potable water, wastewater, roads and bridges, solid waste, sports facilities and public transit in every major urban centre in the country. Conducted for the Federation of Canadian Municipalities and seven partner organizations, it’s an ominous document that proves that Calgary hardly stands alone with its shoddy pipes and roads. A major failure could be coming to a city near you real soon.

The report states that a significant amount of public infrastructure in Canada is “aging and in poor condition” and that there is an urgent need for long-term investments in infrastructure renewal. It includes roads, bridges, libraries, and arenas – the very things Canadians rely on every day. Across the country:

- Nearly 40 percent of roads and bridges are in fair, poor, or very poor condition, and roughly 80 percent are more than 20 years old.

- Between 30 and 35 percent of recreational and cultural facilities are in fair, poor or very poor condition. In some categories (such as pools, libraries and community centres), more than 60 percent are at least 20 years old.

- Thirty percent of water infrastructure (such as watermains and sewers) is in fair, poor or very poor condition.

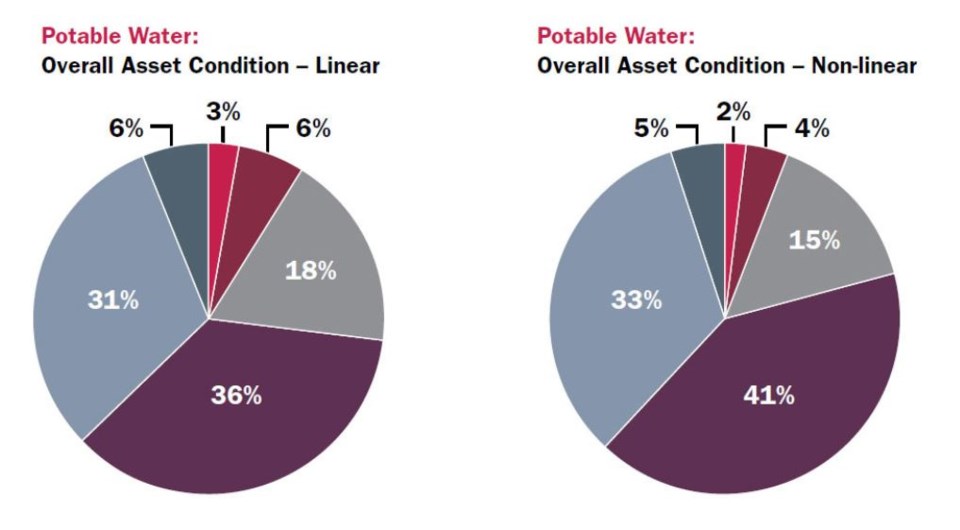

Let’s dwell on that last item for a minute since it’s in the news. The survey looked at linear (local water and transmission pipes) and non-linear assets (water treatment facilities, water pumping stations, and water reservoirs). The chart below summarizes the findings:

In all, the infrastructure deficit in Canadian cities is estimated, at minimum, . Yet, even though the infrastructure report card is from 2019, action has been slow in coming, including an underwhelming commitment in the federal government’s 2023 budget. An article in online academic magazine by Kerry Black, an assistant professor and research chair in sustainable communities at the University of Calgary, summed it up this way:

“Budget 2023 provides no new major funds for what is considered essential community infrastructure: roads, water, wastewater and other infrastructure assets. Unlike electrification and connectivity – many aspects of Canada’s infrastructure gap remain relegated to low-priority status.”

In other words, infrastructure is not sexy; it doesn’t win many votes, and it’s too expensive for cash-strapped governments to take on. Don’t expect a big fix any time soon.

Today, Calgary. Tomorrow, perhaps St. John’s or Victoria or Toronto. Aging infrastructure will break, and fixing it during a crisis is a lot more expensive than if the problem had been short-circuited in the first place.

Too bad politicians, who live by the four-year election cycle, can’t be convinced to make it a higher priority.

Doug Firby is an award-winning editorial writer with over four decades of experience working for newspapers, magazines and online publications in Ontario and western Canada. Previously, he served as Editorial Page Editor at the Calgary Herald.

©