A decline in farmland values could be lurking around the corner for the first time in decades, say a couple of experts.

“We do have potential for a correction,” said Ted Cawkwell, owner of Cawkwell Group, a Saskatchewan realtor.

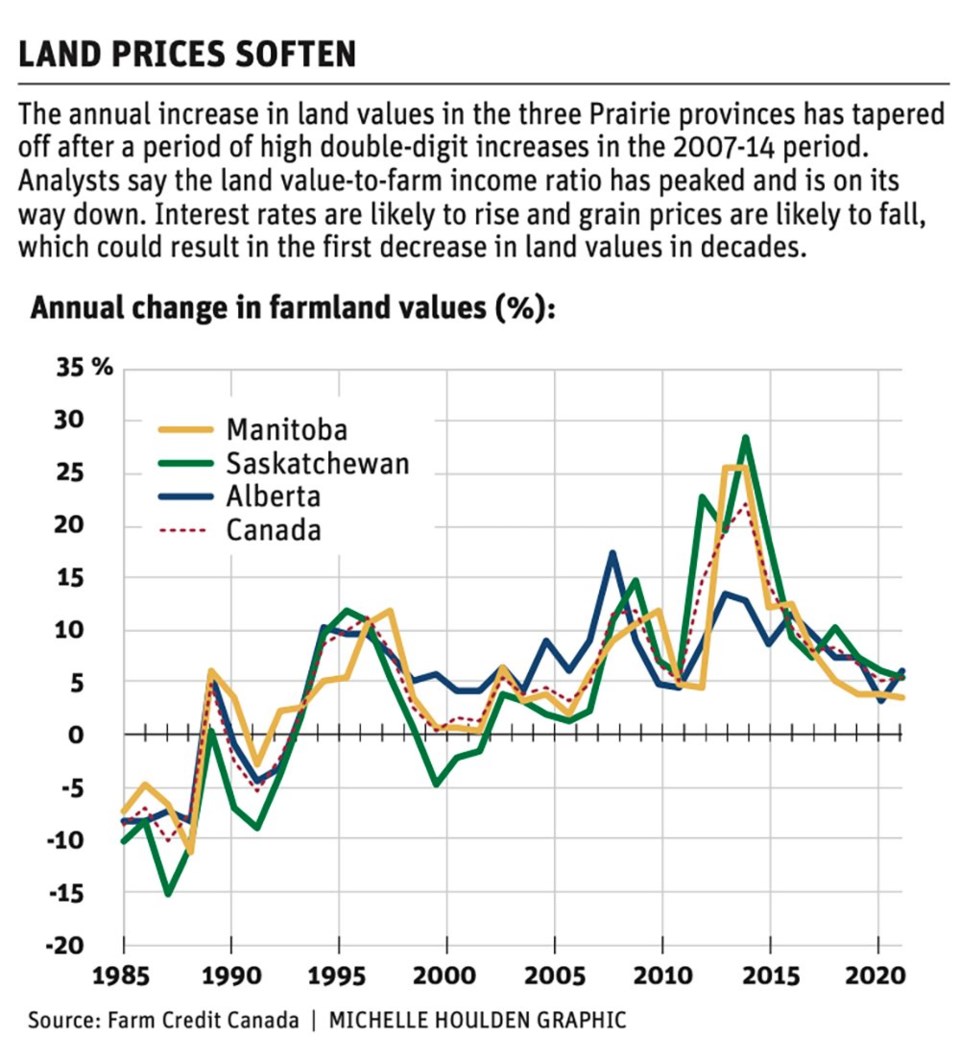

The last time farmland values dropped in that province was 2001. For Alberta and Manitoba, the last reductions occurred in 1992 and 1991 respectively.

There have been phenomenal double-digit increases in annual value over the past two to three decades but during the past five years it has tapered off to single-digit levels.

Farmland values are largely determined by two factors — interest rates and farm income. Interest rates have been phenomenally low and grain prices are at record-high levels.

“The interest rates don’t have anywhere to go but up and the commodity prices don’t have anywhere to go but down,” said Cawkwell.

Another factor to consider is this year’s devastating drought. It will have a negative impact on farm income, especially if it turns into a multi-year drought like happened in the 1980s and 1930s.

That could depress Saskatchewan farmland values in 2022.

But he doubts it would be a province-wide devaluation. It is more likely to occur in pockets where there is severe drought or in areas like the Regina Plains where values are high compared to the rest of the province.

J.P. Gervais, chief agricultural economist with Farm Credit Canada, also wonders if the minus sign will make an appearance in next year’s FCC Farmland Values Report.

“I do think it’s possible. I don’t think it’s probable,” he said.

What worries him is that the ratio of land prices to farm income is at a historic high point, which means there is little room to grow further.

“We’re at the top of the cycle for sure,” said Gervais.

He too wonders if commodity prices and interest rates are at a tipping point, which could result in a weakening of that key ratio.

Gervais thinks the Bank of Canada rate could go up by as much as one percentage point by the end of 2022.

Scotiabank is calling for a two percentage point hike by the end of 2023, which would cause banks’ prime lending rates to rise by the same amount.

Gervais said that would act as an anchor on farmland values.

Cawkwell believes commodity prices would be the bigger factor as evidenced in the first half of 2021.

Just when analysts thought farmland values were starting to peter out they exploded in early 2021 as growers were suddenly selling canola for $20 per bushel.

“Things were going absolutely crazy,” he said.

“We were seeing areas where farmland was valued at $2,000 per acre selling for $3,000 per acre.”

Record-high commodity prices had growers brimming with optimism. And then the drought hit and the double-digit increases vanished as fast as they had appeared.

That is a prime example of how even perceived changes in farm income can have a profound impact on land values.

Despite some of the mounting headwinds in the farm sector and the potential for a market correction, Cawkwell remained bullish about farmland values in the long-term.

He said any downturn will likely only last two or three years because farms are cash- and equity-rich after a good 10-year run in agriculture. Producers should be able to withstand a temporary downturn in the farm economy and return to buying land.

Moreover, the fundamentals in agriculture are too strong based on the ever-expanding world population and the intrinsic value of Saskatchewan farmland.

“You can’t buy land with this productivity at this price anywhere else that I know of,” said Cawkwell.