REGINA — Bill Schroeder was told to halt his genetic work at the Prairie Shelterbelt Centre when the then-Conservative federal government closed the Indian Head, Sask. facility in 2013.

The gene pool of hardy prairie trees that had been developed there since the 1880s was deemed unneeded.

“I was told to discontinue my program and move on to new things that were more important,” Schroeder said in an interview.

The words “climate change” and “shelterbelts” weren’t to be used and he worried that the genetic material he and so many others had worked on would be lost.

He and well-known local conservationist Lorne Scott decided to take matters into their own hands. They moved some of those genetics to a safe place.

“What safer place than Lorne Scott’s?” Schroeder said. “It was totally under the table, of course.”

But 10 years later, with those trees growing in a park-like setting, he feels comfortable sharing the secret and hopes others will appreciate that the work of more than 100 years lives on in some way.

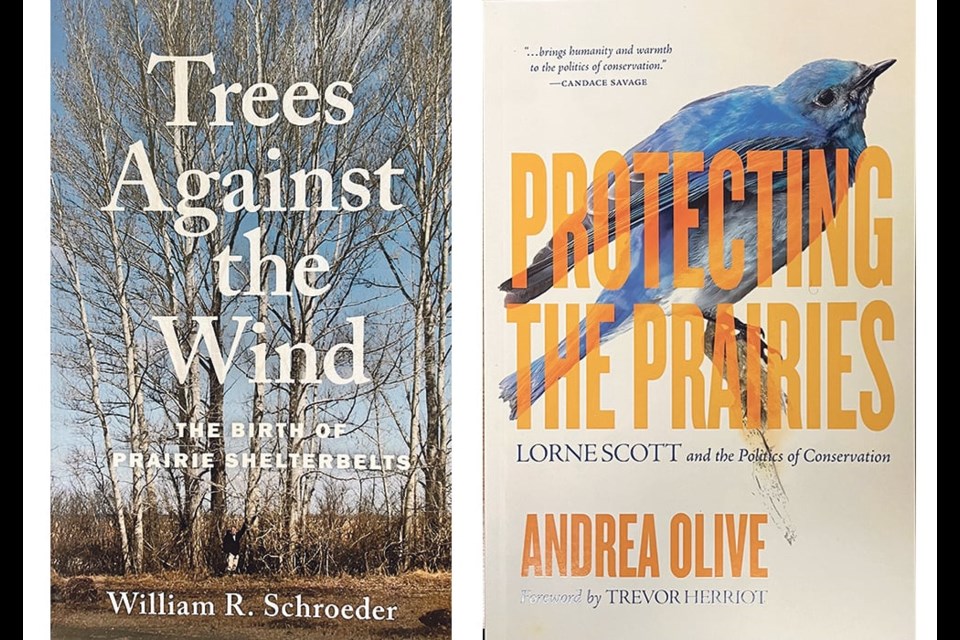

Schroeder has published a book, Trees Against the Wind: The Birth of Prairie Shelterbelts, that documents the establishment of the Indian Head centre and its first 40 years. The last chapter is devoted to its demise 112 years later.

He said he wrote the book because trees no longer seem to have much priority on the landscape.

“I always thought that history is really what helps us plan the future,” he said. “The other thing is that I still talk to farmers almost every day about tree problems or about what tree they should plant and what got me is that the farmers always can remember exactly what year, sometimes even the day, they planted their trees.”

Schroeder said farmers of all political stripes say they miss the nursery that offered free seedlings for farmyards and shelterbelts so he thought he’d share some of its history.

The program began after Parliament decided to establish experimental farms to ensure proper varieties and practices for incoming farmers. Legislation was passed in 1886.

In his book, Schroeder examines how the government of the day thought trees were necessary to attract settlers and keep them there, and he focuses on Norman M. Ross, who took charge of the new shelterbelt centre in 1901 and stayed until 1941.

“I thought people would like to know how a person by the name of Norman MacKenzie Ross was able to take a program and build it into something that would become the longest continually running government program, soon to be outdone by income tax I think, but a tremendously popular program,” said Schroeder.

The book also notes an earlier attempt to shut down the tree nursery.

On the Scott farm, which is protected by a conservation easement, grow about 85 varieties of 30 to 40 species. Schroeder sells tree seeds from those genetics through an online business.

Carry the Kettle Nakoda Nation owns the former shelterbelt property now, where three to four million tree seedlings in the ground when it closed are now growing wild. The band had plans for the centre but it’s a tough business, even though Schroeder said he works with many farmers and acreage owners who want to establish or re-establish shelterbelts.

“But how do you convince an innovative farmer that thinks it would be a good idea to do it when it would cost him thousands and thousands of dollars?” he said.

His book is published by Nature Saskatchewan.

Scott’s involvement in the surreptitious removal of tree seedlings notwithstanding, he has been a legitimate force for conservation and the environment in Saskatchewan for his entire life.

A new book by Regina native Andrea Olive tells his story.

“She did an amazing job with who she had to work with, that’s about all I can say,” Scott said during a book sale.

Protecting the Prairies: Lorne Scott and the Politics of Conservation entwines his personal and political milestones, from a young boy fascinated with bluebirds to his work at the Saskatchewan Wildlife Federation and as an NDP environment minister.

Some might not know that Scott’s first political membership was actually in the Progressive Conservative party as he sought to keep public lands public.

In 1981, he went to his local PC MLA, Graham Taylor, to get help. Taylor raised the matter in the legislature and told Scott he had to buy a membership to put the matter on the party’s convention floor.

The resolution passed with 83 percent support and the PCs won government in 1982. Scott said he and others worked well with the new administration, helping secure 3.5 million wildlife habitat acres that would never be broken or sold.

“It took another 10 or 15 years before the 3.5 million acres was all in the act,” Scott said.

But along came the Rafferty-Alameda dam conflict and more politics. Scott was asked to run for the NDP.

“I showed (leader Roy) Romanow my expired Conservative membership and he said that doesn’t matter,” said Scott.

In fact, Scott had never been active in any political party, but he had been president of the SWF and worked with Nature Saskatchewan and other organizations.

“I decided to take the plunge, and I won. And won again in ’95,” he recalled.

He became environment minister and politics were his life for the next four years.

After that stint he returned to the SWF as executive director, and the politics of game farming and the federal gun registry took centre stage. And of course he was involved in trying to save the Indian Head shelterbelt centre and keep community pastures as public lands.

“We did have a victory in the pasture and the province agreed not to sell them, even though they had offers for people to buy them,” he said. “The producers are managing them and quite well, and they cannot be sold or broken up so that was a victory.”

Still, Scott says conservation efforts are falling behind.

“We’re further behind than we were 40, 50 years ago, partly because there is less opportunity to preserve and work with wildlife and there’s a bigger emphasis on development. The whole rural landscape is changing with fewer and fewer farms,” he said.

He believes farmers operating on extremely large acreages aren’t as in touch with the land as farmers used to be.

“They don’t notice or they don’t care about the wetland in the corner of a quarter section or a shelterbelt that’s been there for 100 years.”

And he doesn’t think that will change unless more farmers put conservation easements on their land.

“It’s sad. We have room for everything, lots of farms but some habitat for wildlife as well.”

Olive’s book is published by University of Regina Press.

There are no Holsteins in a new children’s book about a ranch.

Katelyn Toney, Saskatchewan producer and mother of four, has self-published her first book, On the Busy Old Ranch.

The 20-page board book is designed to show real ranch life, she said. The idea came from reading to her own children.

“They love cowboy stories. I felt like they were either rodeo or very unrealistic of our life and I wanted to write one that was realistic,” Toney said.

The rhyming and counting story goes from one to 10 with different activities, “whether it’s feeding animals or fixing water or moving pairs or loading cows,” she explained. “There’s praying for rain, there’s branding with neighbours at the end.”

The illustrations are by Rebecca Allen from Ontario, whom Toney found on Instagram. Many illustrators weren’t interested because she self-published, but Allen agreed.

“She was wonderful to work with. I sent her thousands of pictures of the Prairies so she could capture real life. She’s never been here.”

The book has been well received, especially from ranch and farm kids.

“They’re so excited to see themselves in it. I read it to the Grades K to 5 in Gull Lake School earlier this year (2023) and it was so much fun,” she said.

Some children had never been on a farm and had many questions. For others, it was old hat but they had suggestions for other ways to do things.

Toney hopes more urban kids will find the book so they can learn more about farming and ranching. It is available in a few stores but can be ordered through .

Her company is called Bluestem Books and she said she has more ideas in the works.