YORKTON - The Yorkton Junior Terriers are celebrating 50 years in the Saskatchewan Junior Hockey League this season.

To mark the milestone Yorkton This Week is digging into its archives and pulling out a random Terrier-related article from the past five decades of reporting on the team, and will be running one each week, just as it originally appeared.

This feature will appear weekly over the entire season in the pages of The Marketplace.

Week #10 comes from Feb. 12, 2000.

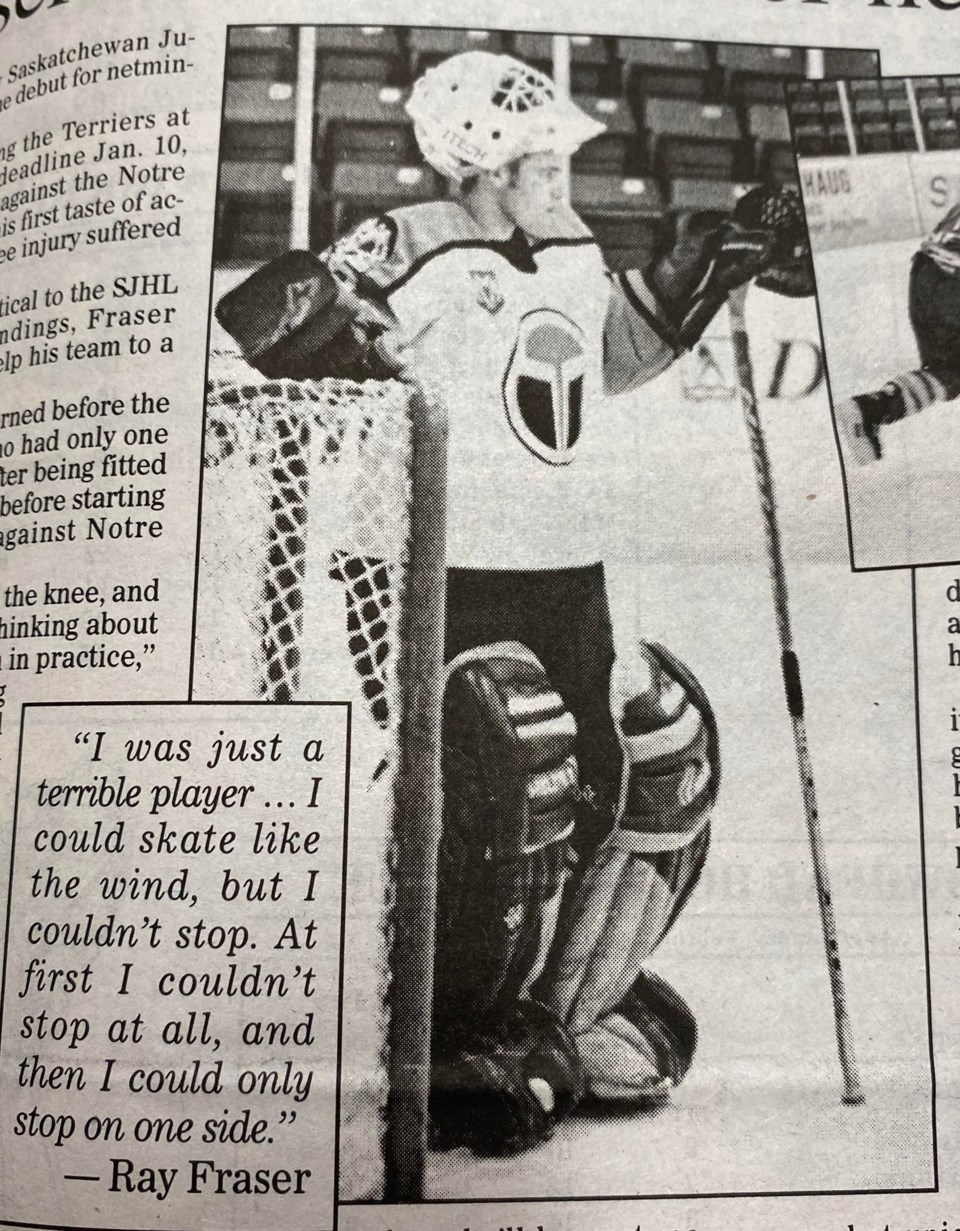

It was a flashy Saskatchewan Junior Hockey League debut for netminder Ray Fraser.

Although joining the Terriers at the trade deadline Jan. 10, Wednesday’s game against the Notre Dame Hounds was his first taste of action, coming off a knee injury suffered in November.

And in a game critical to the SJHL Â鶹ÊÓƵ Division standings, Fraser stopped 31 shots to help his team to a 4-0 shutout victory.

“I was a little concerned before the game,” said Fraser, who had only one full-fledged practice after being fitted with a new knee brace before starting his first SJHL game against Notre Dame Wednesday.

“I was thinking about the knee, and in that extra second of thinking about it I was getting scored on in practice,” he said. “I was thinking too much … I didn’t feel ready to play in practice.”

Then came the call to face the Hounds only hours later.

“Before the game, I was actually quite worried about it,” he said.

And readying for the Hounds’ first shot, the nerves were chattering, he added.

“But once you get into the game you stop thinking, and just start reacting to what goes on around you.”

Less than 12 hours after the win, Fraser said the knee felt good, but his body was fatigued.

“It was quite tiring out there. My legs feel stiff and sore this morning. They’re not used to that kind of movement,” he said.

It was the same thing he felt during the game.

“It was fatigue,” Fraser assured. “I was very tired out there, especially during power plays. It wasn’t the knee bothering me. It was just the fact I was tired.”

The shutout victory helps re-establish Fraser after what has to be termed a trying season of hockey, a season which began in the Western Hockey League.

“The last two years have been difficult for me, but I seem to respond well to adversity,” he said. “Last year going back to Alberta Junior, I was comfortable with it. It was no big deal,” he said, of a year again started in Seattle but ending in Lloydminster.

Then this season he was invited back to the WHL Seattle Thunderbirds, and was hopeful for a relaunch of his career at the level.

“I was disappointed I was traded without even getting a game in in Seattle,” he said.

Still, with a new club in Brandon, a team which obviously wanted him since they traded to get him, looked promising, until the Nov. 5 injury.

“That was probably the hardest thing for me to deal with so far,” he said.

Now with the Terriers, although only on loan from the Alberta Junior Hockey League franchise that holds his Tier II rights, Fraser isn’t sure where he’ll be next season.

As for Brandon, “they’ve told me they want me to go back next year … But I’m not even worrying about it right now.

“I just want to get in better shape and help the Terriers win some games,” he said.

Fraser said the big thing is building confidence with a new team.

“The first couple of games you’re a little nervous. A big part of it is building trust in your teammates and in your coach’s mind and the minds of the fans so they have the confidence in you,” he said.

Fraser said confidence is such a key because “as a goaltender, when you screw up it shows up on the scoreboard.”

In many ways, the inner confidence Fraser has come from a background where he admits hockey was almost abandoned at one point.

“I was always a better baseball player than a hockey player. I had more natural talent for the game,” he said.

As for hockey, in the beginning, Fraser said, “I was just a terrible player … I could skate like the wind, but I couldn’t stop. At first I couldn’t stop at all, and then I could only stop on one side.

“And I wasn’t big enough. I really wasn’t enjoying it.”

Then as a second-year Pee Wee, Fraser convinced his father to let him don the vestments of a goaltender, and he found a home in the game.

“I always wanted to be the catcher in baseball. I guess there was a fascination for all the equipment that drew me to catcher and to goaltending,” he said.

Fraser said when it came to taking the game to the streets, he always wanted to be between the pipes.

“Me and my friends always fought to see who would be goaltender,” he said. “I just always wanted to be a goaltender.”

It might not be a surprise that hockey didn’t come as easily to Fraser given his somewhat unique heritage, at least from the perspective of a hockey player.

Fraser has a slightly different pedigree from most players in the game, having been born in Â鶹ÊÓƵ Africa.

“My whole family’s back there,” he said, as only his parents and his mother’s sister immigrated to Canada when Ray was only 18 months old.

While young enough that Ray was easily assimilated into the Canadian passion for hockey, he admits playing the game has been difficult on his parents, especially his father Hector.

“It was hard for my dad. He knew absolutely nothing about the sport … He couldn’t get out and show me what to do. He can’t even skate,” he said.

But that hasn’t prevented Fraser’s parents from being supportive of his on-ice efforts.

“My parents have made a lot of sacrifices for me to play hockey,” he said.

In his dad’s case, he was always there.

“He was the type of dad that came to every game and practice. There were lots of times he was the only guy in the stands watching practice. I’m very thankful for the support … he was always there for me,” he said.

Fraser’s mom took a different approach, but no less supportive.

“My mom never goes to games very often. Every time she comes to a game, I get hurt,” he said. “But she always believes in me.

“Even when dad looks around at all the other top-notch goaltenders and starts to wonder … she always says I can do it.”

He’s also a netminder minus the quirks often associated with his breathen, focusing instead on just doing his job.

“I just like to stretch out before games, and I like to listen to music in the room. I’m as normal as they come for goaltenders,” said Fraser.

That being said, Fraser still repeatedly skates to the corners after stoppages in play.

“It helps to keep me loose. It gives me a break from thinking about the play,” he said. “It’s a chance to refocus.”

Even his mask is still plain white, never having been adorned with the illustrations most netminders have these days. When asked why, Fraser summed it up with a laugh.

“Money, I guess,” he said. “When I was younger, I wanted the nice equipment and the helmet all painted,” he said. “I always wanted to look good. It was always about the show … It’s kind of embarrassing, looking back.

“But I’ve got to the point I could care less. You could throw me out there with used phone books for pads. I don’t really care.”

While he’s never used phone books, Fraser admits he’s never had ready access to new equipment because of the costs.

Fraser recalls starting out using the old equipment of the other goaltender on his team.

“It was a really bad chest protector, and I was coming home with bruises all the time,” he said.

Fraser admits his father wasn’t keen on his decision to become a netminder, but once between the pipes, “he respected me for actually staying in there.”

But through it all, Fraser has persevered and still dreams of the game.

“The NHL is always in the back of everybody’s mind. It’s the dream of every kid that steps on the ice,” he said.

But coming off an injury and having played for four teams in three leagues in two seasons, Fraser has narrowed his focus to shorter-term goals.

“I still want to go as far as I can in hockey, but I want to get my education too,” he said.

“I’m no fool. If somebody offers me a million dollars to stop pucks, I’m going to take it, but I want an education.”