YORKTON - Increasingly it seems sports books are looking beyond the in-game action and stats, to tell a larger story of the world around the game as well.

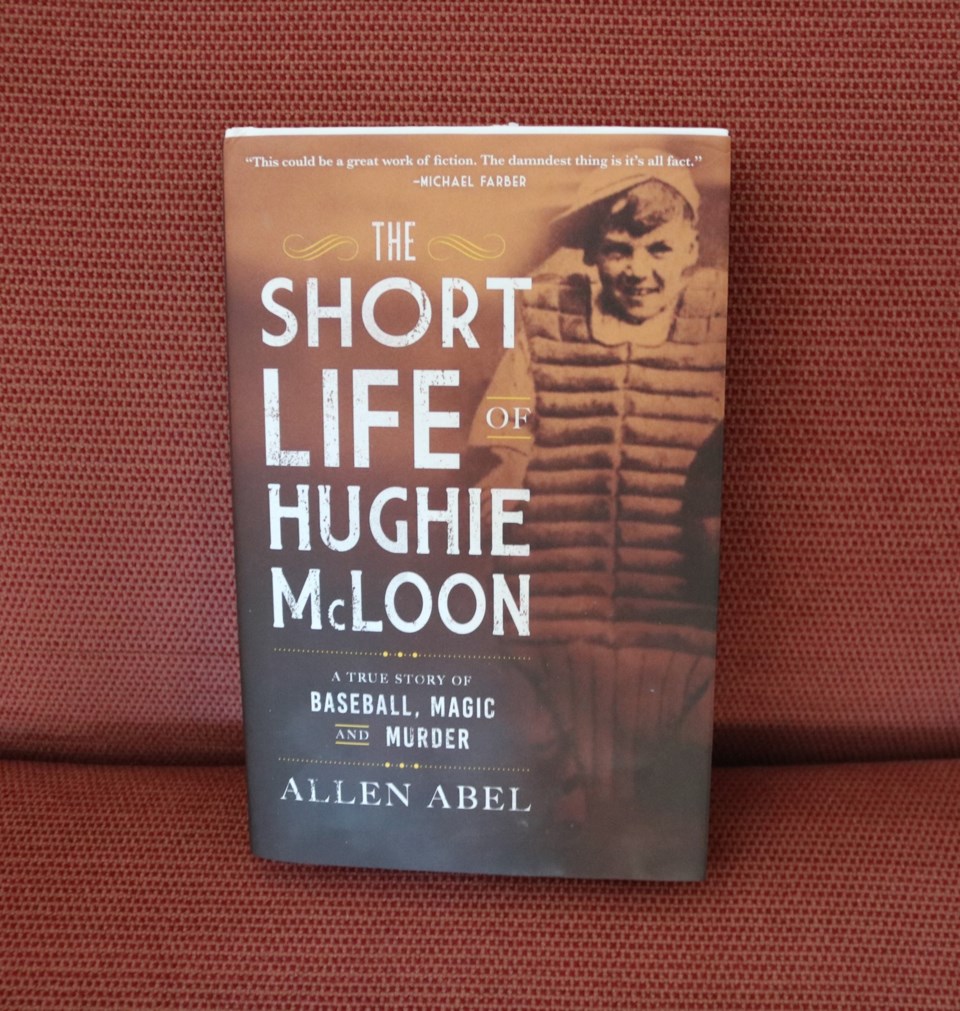

At least that has been the case with several recent sports books I have enjoyed including The Short Life of Hughie McLoon by Allen Abel.

The book is billed a story of baseball, magic and murder, and manages to be about all three even as it is a non-fiction story.

So who was McLoon, and what exactly is the story here?

The publisher’s page at sutherlandhousebooks.com wets the appetite for the book nicely.

“It was a time of Prohibition, jazz, and gangland murder, and it was baseball’s age of magic, when even Hall of Fame superstars believed that rubbing the hump of a hunchback guaranteed a hit,” it details.

“Deformed for life from a childhood fall from a seesaw, Hughie McLoon never grew taller than fifty inches, but destiny and snappy wit made him the most envied boy in Philadelphia — the batboy and mascot of Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics. Although the A’s finished last in each of the three seasons that they rubbed Hughie’s hump and he tended their bats, McLoon became a local celebrity. He loved the crowds and they loved him back.

“Graduating from disabled mascot to professional boxing manager, and running his own speakeasy while serving as a secret agent for the city’s crime-busting director of Public Safety, Hughie was the toast of Philly until one August night in 1928 when he was caught in a midnight crossfire outside his tavern. Only twenty-six years old, McLoon bled to death on Cuthbert Street. The next day, 15,000 citizens lined up to see his four-foot corpse. The age of magic was over.

“A century ago an American boy in a broken body lived a leprechaun’s life and died a gangster’s death. The Short Life of Hughie McLoon is Allen Abel’s haunting and stylish biography of the most remarkable and beloved of the baseball mascots — the history of an era that will never come again.”

It’s frankly the stuff of Hollywood without the usual embellishments of movie writers.

From a baseball fan’s perspective as reader, this was the sport at a very different time in its history.

“Professional league baseball was only a quarter-century old at the hour of Hughie McLoon’s birth but everything beautiful about the game already was in place: the hurry, Dad walk with the crowd from the streetcar; the sudden, perfect green of the grass against the city’s grime; the filling grandstand and joshing athletes in their monogrammed flannels; the hurling, the slugging, the sliding, the roaring, the heckling; the game’s deep lode of custom, statistics, and lore,” writes Abel in the book.

But it was a darker time too.

“The game’s popularity masked its less appealing facets, including rampant game-fixing, virulent racism, lifetime contractual bondage, players staggering around drunk during games, and rubbing a teenaged hunchback’s deformity (or a young African American’s head) for luck on the way to home plate. Most players’ salaries were minimal, illicit gambling was universal – Rube Waddell was known to leap into the stands to pummel taunting bettors – and the corporate structure of the two major leagues virtually defined the word “monopsony.”

But this is a book about a young man whose connection to the game was frankly a touch unsettling.

“Hughie McLoon had vaulted onto the ball fields and the sports pages of Philadelphia in the terrible July of 1916, when, as a skinny, crippled, irrepressible eighth-grader at Our Lady of Mount Carmel School, he was cast for the role that would be carved into his headstone a dozen summers later; the living talisman of the greatest baseball team in the universe,” wrote Abel.

As unbelievable as it might be today, young boys with deformed backs, often became a sort of ‘lucky penny’ where they would be touched by players striding to the plate as a talisman to getting a hit, explained Abel in the interview with YTW.

Author Abel spent considerable effort collecting nuggets about McLoon from any source he could find to build the story. It is something he was well-suited too given his work has appeared in Sports Illustrated, Smithsonian, and the Globe & Mail. He has written, produced, and hosted broadcasts and documentaries for HBO, the Discovery Channel, and the CBC.

In a chat about the book Abel said when it came to his research he found no letters, no diary to help tell McLoon’s story.

And even distant relatives found knew nothing of the man gunned down in the street in Philly years earlier.

There were lots of newspaper printed in the day, and they became Abel’s primary source yet even then most of the material “was after he was killed,” noted Abel.

While Abel said he is proud of the book as a non-fiction work, he did provide a note of caution that not every word may be the gospel truth, noting newspapers of the era were prone to exaggeration at times to sell papers so stories would contradict each other.

But, from the facts of the press of the day it is the story of McLoon’s slightly surreal life and death.

It is the death where the book starts, hooking the reader quickly.

“Hughie McLoon walked out of the speakeasy at a quarter to two in the morning with a hoodlum on each arm. Here he was, the most recognized and popular little guy in Philadelphia – hadn’t they asked him to hold up the round cards at the Dempsey-Tunney fight with 130,000 people in the stands? – and now he was running his own café at Tenth & Cuthbert, five short blocks from Independence Hall and the Liberty Bell, and life should have been, as they said in those days, the berries,” wrote Abel.

“McLoon was serving sandwiches, “light lunch,” and bootleg ale and whiskey ladled from buckets secreted behind the counter when two wise guys with names off a Hofbrau menu, Meister and Fries, imposed themselves. They were into their beer even before they’d hauled up and now, more having been applied, they began bradding loudly about things they’d done and girls they’d ravished and people they knew around town. Hughie decided to invite his guests into Philadelphia’s summer air, lest the scene become more indecorous.

“Just then a car, later identified (rather unhelpfully) as a “black machine” or “a big sedan,” came busting down Arch Street. It swerved southbound on Tenth, and braked sharply in front of the three men. A gun poking through the left rear window ended the short life of Hughie McLoon.”

It sounds bigger than reality, but it is not.

“What’s important to me, it’s all true,” said Abel. “I wanted it to be a work of journalism.”

Abel added at his first reporter posting in Albany years ago there was a sort of motto; ‘find out everything you can. Print everything you find.’

That was his approach for the book, he added, and it worked. This was a great read full of history, darkness, intrigue, and all the sadness of one young man’s short life.