SASKATOON — Stripped of their culture and identity, Eugene Arcand will never forget how he became nothing but a number when he joined other Indigenous children forced to attend the residential school system.

Arcand said the road is still a long one for those survivors who are still living and he wants to make sure everyone who supports them “walk the talk” as he called for acknowledge of Indigenous elders who managed to come home.

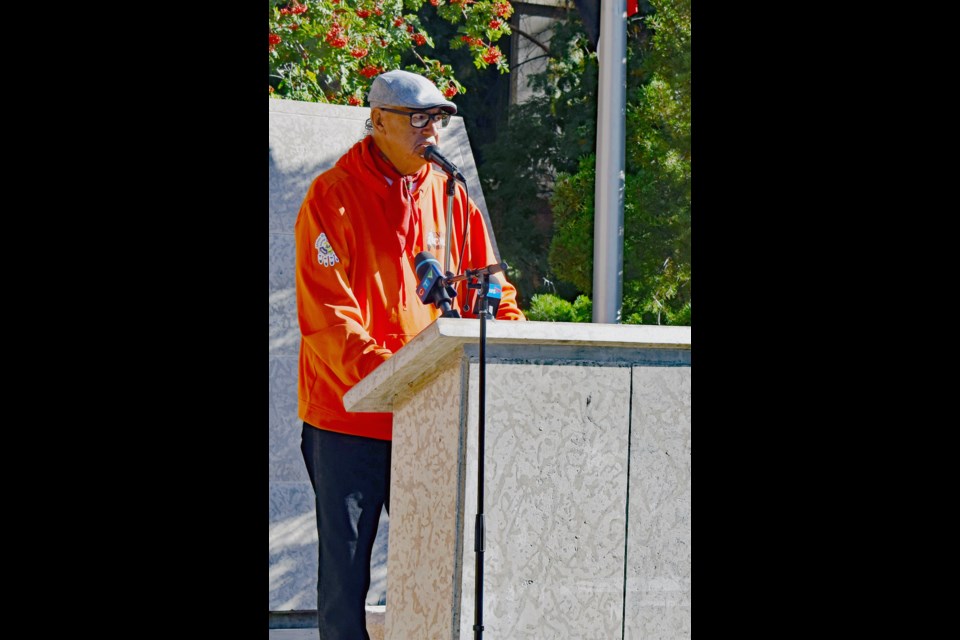

“We’re real human beings that want to share our horrible experiences, not for pity, not for people to feel sorry for us, but so that everyone understands,” said Arcand during the unveiling of the Survivors’ Flag on Monday, Sept. 26, at the City of Saskatoon Civic Square.

“We’re here. We want to share the truth, which leads to reconciliation. Get to know us, don’t just talk about us. We’re not numbers anymore and we’re not owned anymore. My number was 781 and we all have a number ingrained in our hearts and minds.”

He encouraged Premier Scott Moe and the provincial government to acknowledge the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, since a large number of residential school survivors are from Saskatchewan.

“The raising of our [survivor’s] flag on this second anniversary of what is publicly known as Truth and Reconciliation Day in Canada, but for us residential school survivors it will always be Orange Shirt Day,” said Arcand.

“I would also like to encourage the premier and the government of this province to grow up and start recognizing this day for next year. It is shameful when we have 33 per cent of all residential school survivors in this country are from this province and we don’t acknowledge this day.”

The stories of abuses in residential schools are one of the darkest parts of Canada’s history, particularly during the Sixties Scoop when thousands of Indigenous children were forcibly taken from their families and communities to assimilate them into western culture.

Students, especially Indigenous children, were forbidden to speak their language and practice their culture while at residential schools — to eliminate the “Indian” in them. Their hair was cut short and they were punished when caught speaking their native language.

One of those stories is that of Phyllis Jack Webstad who shared that arriving as a six-year-old at St. Joseph Mission in Williams Lake, British Columbia, she was stripped of her clothes including the new orange shirt given by her grandmother.

The orange shirt is now the colour that is associated with how the culture and identities of Indigenous children were taken away from them. The Orange Shirt Day is held every Sept. 30 to commemorate the legacy of the Canadian residential school system.

The Survivors’ Flag project started about four years ago after a group of residential school survivors found out that other people were profiting off of their harmful stories and misery, with some flags being made as far as Indonesia with the words “Every Child Matters.”

“Someone was getting rich off it. There are various companies out there that were profiting from 'Every Child Matters.' We want to remind them that is not just a slogan. It’s for real and every child matters,” said Arcand.

“It’s time people start understanding that. By wearing the shirt, you are not only supporting us. You’re also recognizing every child does matter … This flag [is] going to remind people to do things the right way.”

The Survivors’ Flag symbols

The Survivors’ Flag, which is orange in colour, honours all residential school survivors along with the lives and communities that were affected by it. The elements drawn on the flag are symbols selected by survivors across the country.

It has a four-person family, symbolizing their ancestors watching over them, while others see this as signifying families reunited after their children were forcibly taken away.

It also has the Tree of Peace, the Haudenosaunee symbol of how First Nations were united, which in turn provides comfort, protection and renewal. There is also a seed underground representing the spirit of Indigenous children that never returned.

A cedar tree is a sacred medicine to Indigenous Peoples as it represents healing and protection, but it is also used in some First Nations cultures as a medicine bath when one enters the physical world and then when they pass on to the next.

The seven branches represent the seven sacred teachings — wisdom, love, respect, bravery, honesty, humility and truth — that are taught in many Indigenous cultures. Cosmic symbols — sun, moon, stars and planets — is for divine protection to the survivors.

The north star is a prominent navigational guide for many Indigenous cultures while the eagle feather represents the Creator’s spirit in everyone and it points upward mirroring how it is held when one speaks the truth.

The Métis sash is ceremonial regalia worn with pride with the colours of the thread representing the lives that were lost, our connection as human beings and resilience through trauma. Lastly, the Inuksuit are used by Inuit People as navigational guides connected to tradition.