Between 1905 and 1909, the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway completed its transcontinental railway between Winnipeg and Edmonton. By January 1909, it announced its plan to construct a network of branch lines throughout Saskatchewan. Once such branch was a 30-mile line from the town of Yorkton north to the village of Canora. Â

The country through which the branch would pass was predominantly low, nearly level, wet prairie grassland dotted with bluffs of small popular and clumps of willow, with numerous sloughs and marshes, much of which was alkaline, and broken land associated with the Whitesand River and its tributaries, the Little Whitesand River (Yorkton creek) and Boggy Creek (Wallace Creek) over which it crossed. It was well-settled with English, German, Polish and Ukrainian farmers cultivating adjacent lands.

By January 1910, GTPR surveyors staked the line right-of-way, and following its approval by the Board of Railway Commissioners in February, the company issued tenders for line clearing, grading, track-laying, bridge-building, fencing and telegraph construction. In March, a contract was awarded to the Doukhobor organization, the Christian Community of Universal Brotherhood, for clearing and grading the line.

The contract marked a milestone for the Doukhobor Community. From 1899 to 1909, thousands of Doukhobors were employed as ‘navvies’ or railroad construction workers each year to earn much-need income. Indeed, it was a workforce of 1,000 Doukhobors that constructed the Canadian Northern Railway line from Kamsack to Humboldt that led to the formation of Canora in 1904. However, this would mark the first time they would engage in railway building as an independent contractor.

For their part, the Doukhobors were well positioned to carry out the contract. In 1910, the Community had a large, experienced workforce of men, along with draft horses, oxen, tools and equipment within a day’s journey of the work.

The value of the contract was enormous by the standards of the day. Upon completion of the work, the Doukhobor Community would be paid the sum of $70,000. This amounted to $2,300 per mile.

However, the contract also had an aggressive deadline. The GTPR expected the grade to be completed by autumn. However, the Doukhobors had to finish spring seeding before they could begin the work and had to return to their villages by late summer for haying and harvesting. Doukhobor leaders needed to plan and schedule the work to be done within these milestones, a narrow window of two months.

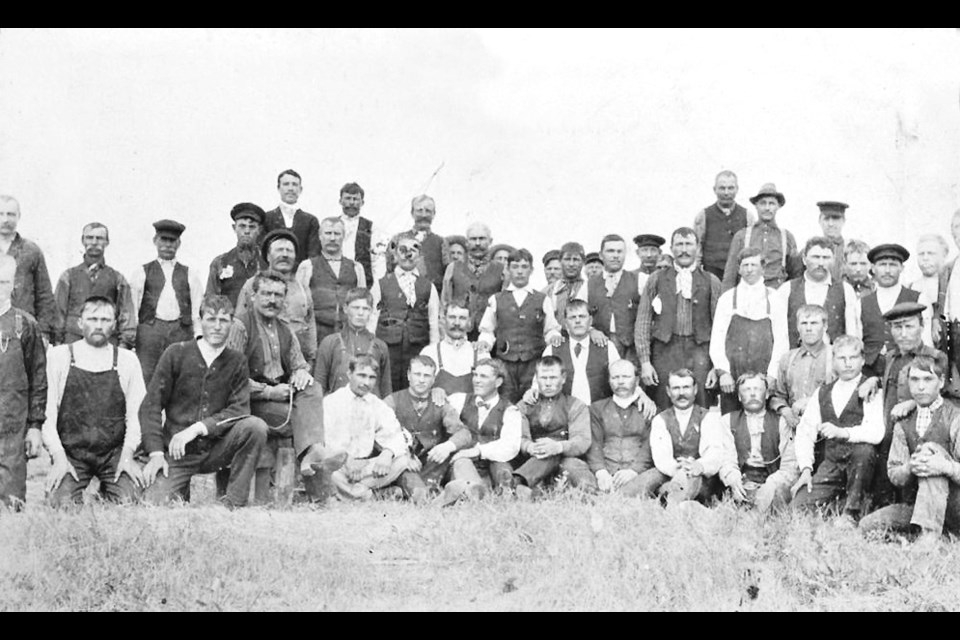

Thus in mid-May, following spring sowing, 1,000 Doukhobor workmen left their villages in the Buchanan, Canora, Verigin, Kamsack and Pelly districts and converged on Yorkton to begin the work. They brought all of their own tools and equipment, including 800 head of horses, hundreds of scrapers, dump carts, wheelbarrow and spades as well as milking cows, temporary shelters, food and livestock feed.

The Doukhobors organized themselves into 10-12 camps of about 80 men each, which were set up at roughly 1-2 mile intervals along the line route. Each camp had 7-8 ten-man tents for the men to sleep in, one tent for the women, a store tent for supplies, another for the cook house and mess hall, one for a portable blacksmith along with makeshift stables for the 30-40 teams of horses at each camp.

Within each camp, duties were well-ordered and systematically carried out. Men were designated as cooks to bake bread and cook borsch over makeshift ovens built using local clay and stone. Others were assigned to cut, split and stack cordwood for the cookhouse or construct benches for mess halls. The blacksmiths built makeshift forges lined with fieldstone and using poplar logs to make charcoal. Women washed and mended clothing for the men in their tents while others milked cows. At the outdoor stable, some prepared feed for the horses by chopping and soaking bailed hay then mixing it with oats. Indeed, the Yorkton Enterprise reported that the Doukhobors bought up all the available feed oats for ten miles on either side of the line. Others hauled drinking water from creeks and wells for the men and animals.

At each encampment, Doukhobors were organized into work gangs responsible for clearing, making cuttings and fills or building the earthen embankment or grade. Tasks and work flows were carried out in an organized and disciplined manner, closely resembling a hive of bees.

Clearing was done almost entirely by hand, using hatchets, axes, saws, pick axes and spades. Large rocks and tree roots were moved by hand or with horses and chains. Low alkaline wetlands and muskeg, common throughout the route, were drained by digging trenches and then filled with rocks and soil.

The embankment needed to be sold and permanent, requiring little maintenance or upgrading. It also needed to be straight and level to allow trains to run at full speed at all times. It also had to be raised to allow for adequate drainage. Based on these specifications, the Doukhobors built an eight-foot wide grade averaging four feet high on level ground and as high as 15 to 20 feet in low areas. This was done using hundreds of teams of horse-drawn scrapers and dump carts, labouring alongside gangs of men with spades and wheelbarrows, who excavated a ‘cutting’ on either side of the embankment. The excavated soil was then dumped at the head of the raised earthen embankment.

Labouring from 5:00 a.m. to midnight each day, the work crews built the grade up and forward, advancing steadily north. By late June, they reached the banks of the Whitesand. And by late July, the Canora Advertiser reported that the grade had reached Canora. There, most of the workmen returned to their villages for haying and harvest.

Remarkably, the Doukhobors, using only horsepower and manual labour, cleared and constructed 30 miles of grade, moving over five million cubic feet of earth, in only 69 days, at a rate of nearly half a mile of grade per day. Â

After the grade was completed, a track-laying crew soon followed. By August, other crews installed fencing and telegraph lines along the route, raised a trestle bridge across the Whitesand and constructed a GTPR station at Canora. By October, the first freight came over the line by steam engine.

The arrival of the GTPR was a tremendous boon to Yorkton, further escalating its development and ensuring its place a major regional rail hub. The city now had direct rail access to the north of the province.

The line also resulted in the formation of new communities, with GTPR engineers surveying townsites and sidings at regular intervals along the line. Thus, Young’s Siding, Mehan, Pollock’s Spur, the village of Ebenezer, the hamlet of Gorlitz and Burgis all became important new grain-shipping points.

The toil and industry of the Doukhobor railway builders not only benefitted their immediate Community, it also helped develop the surrounding region through the extension of transportation infrastructure, establishment of shipping and commercial hubs and the founding of new settlements.