WESTERN PRODUCER — About eight years ago, Aaron Hager warned farmers in Alberta about palmer amaranth.

Hager, a University of Illinois weed scientist, spoke to growers at a conference in the Peace River region. He explained that palmer, a pigweed that grows to two metres or higher, could be viable in Alberta and other parts of Western Canada.

“We don’t know the (geographic) limits of that species,” said Hager.

“The question is not to ask ‘if’, but ‘when.’”

Palmer amaranth is well known to American farmers — it is now established in most agricultural states. The weed is infamous for producing up to a million seeds per plant and quickly developing resistance to herbicides.

“Palmer amaranth’s prolonged emergence period, rapid growth rate, prolific seed production and propensity to evolve herbicide resistance quickly makes this the most pernicious, noxious and serious weed threat that North Dakota farmers have ever faced,” said Rich Zollinger, a retired weed scientist with North Dakota State University.

This would indicate that palmer with resistance to multiple herbicides could represent a serious problem for prairie farmers.

The pernicious weed hasn’t yet been detected in Alberta or Saskatchewan. Manitoba recorded its first case in 2021, when it was found in the Rural Municipality of Dufferin.

However, central and northern Alberta is a long way from southern Manitoba and even farther from states such as Missouri, where scientists have detected palmer amaranth that is resistant to glufosinate, glyphosate and several other herbicidal modes of action.

So, how would a palmer amaranth weed seed travel from southeastern Missouri to central Alberta, a distance of 3,000 kilometres?

One possibility is train.

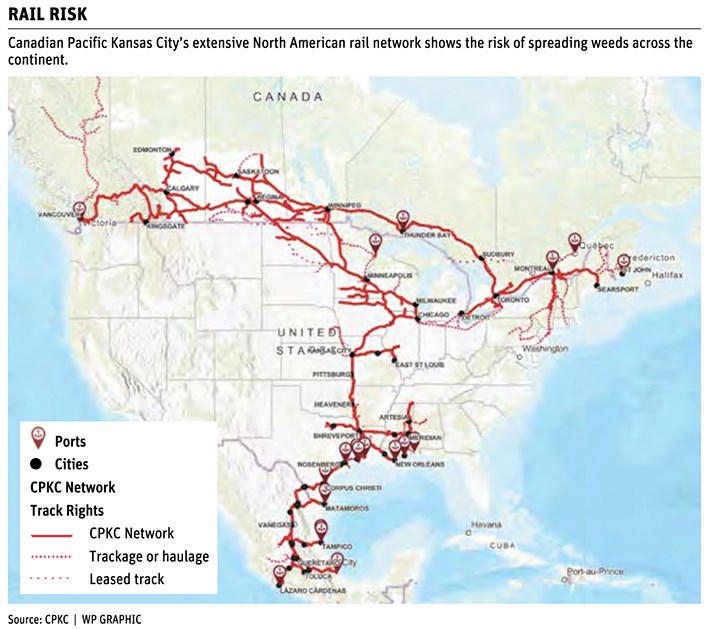

In 2023, Canadian Pacific and Kansas City Â鶹ÊÓƵern railways came together to create CPKC. With the merger, rail cars from the southern United States are more likely to appear in Western Canada.

Those rail cars may contain a shipment of American grain or remnants of a grain shipment at the bottom of a car, which could be contaminated with weed seeds.

In 2016, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency published a paper with the title: .

The CFIA takes samples and tests some shipments of imported grain for contaminants, the report says.

“At the point of import to Canada, inspection sampling data show that grain shipments contain a variety of contaminants including seeds of regulated weeds and species that represent new introductions (of weeds).”

Imported grain that is used for human consumption or industrial uses has a low risk of introducing weed seeds because the seeds are “either removed during cleaning or devitalized during processing,” the report says.

However, screenings of imported grain are higher risk because they contain weed seeds and other non-grain material.

“In Canada, grain screenings are most frequently used as components in livestock feed,” the CFIA says in its 2016 report.

“Screenings that are unprocessed … present a potential risk for the introduction of weed seeds to farm properties and elsewhere. Studies have shown that sheep and steers fed unprocessed grain screenings had viable weed seeds in their manure.”

In an email to the Western Producer, a CFIA spokesperson said the agency continues to test imported grain and screenings for weed seeds and other contaminants.

“This inspection is part of our commitment to ensuring that all agricultural imports comply with Canadian standards and help prevent the introduction of potentially invasive weed species,” the spokesperson said.

“In some situations, the grain arrives cleaned and certified. In other situations the grain arrives for cleaning in Canada and the screening would be either disposed of or processed for animal feed.”

The CFIA doesn’t publish the results of its testing program with details on individual inspections for imported grains and screenings.

More information on CFIA import requirements for screenings and grain for cleaning .

Hager, the University of Illinois weed scientist, said any effort to keep weed seeds and palmer amaranth out of Western Canada is worth the time and money.

“Don’t let those populations become established,” he said.

“Ten years from now, you will be so happy that you did that.”

Related

About the Author