WESTERN PRODUCER — Three regions had extreme rainfall and flooding over the past few weeks across the globe.

In northwest and north-central Africa, unusually persistent and heavy rains caused severe flooding in an area that is usually very dry. In fact, parts of the Sahara Desert and Sahel belt have seen significant rainfall.

The second area of extreme rainfall was across much of central Europe, as an unusually strong upper low dropped southward into Europe, which helped spawn an area of low pressure over the Mediterranean. This low, Storm Boris, pulled plenty of warm moist air northward into Europe, thanks in part to record-setting sea temperatures over the Mediterranean.

The push of moisture northward into the cold upper low, plus lift from mountains, help wring out this moisture, leading to rainfall totals pushing 400 millimetres in some areas. Some areas in Poland, for example, saw triple the previous record total rainfall for September.

The third area of extreme rainfall was in Vietnam, where Typhoon Yagi made landfall on Sept. 7 as a category 4 storm. This was the first category 4 storm to hit this region since modern record keeping began in 1945.

So, while extreme rainfall from typhoons is not unusual, having this strength of a typhoon in the region is unusual. Reports indicate the typhoon did as much as US$2 billion in damage, and at least 291 people died.

Closer to home, three rainfall events hit our part of the world.

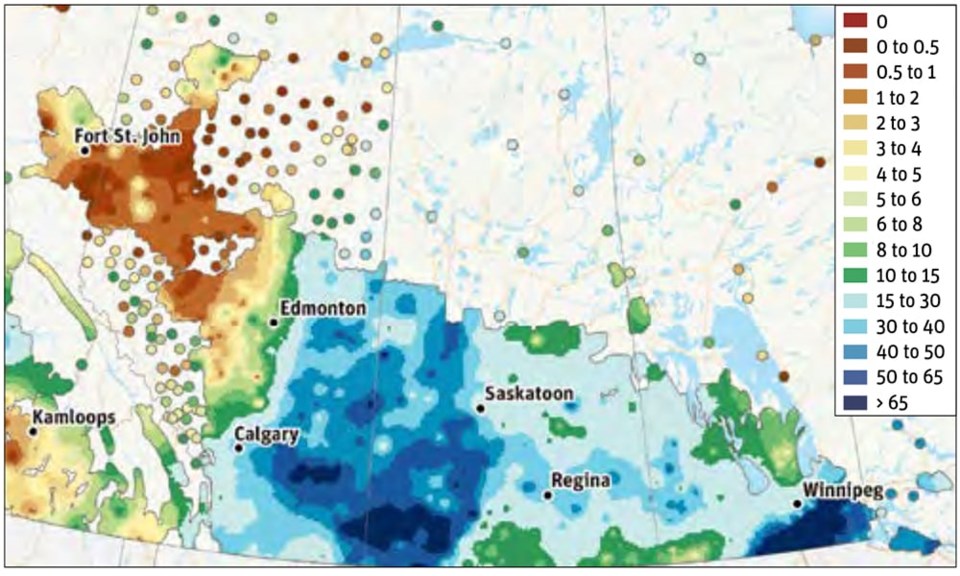

In southeastern and east-central regions of Alberta, widespread amounts of 40 mm to more than 65 mm were reported. This was thanks to a blocking pattern across North America that resulted in areas of low pressure slowly lifting northward into the Prairies, instead of moving relatively quickly to the east or northeast. These rains fell on Sept. 12 and 13.

A few days later, on Sept. 17 and 18, a second area of low pressure lifting northward brought significant rain to much of western Saskatchewan. Amounts from this system were upwards of 65 mm.

This same setup resulted in heavy flooding rain across southeastern Manitoba on Sept. 16 and 17. These rains were the result of a stalled boundary that brought several rounds of thunderstorms that tracked southwest to northeast.

Several storms across the same region, combined with fairly slow motion and unusually high levels of atmospheric moisture for this time of year, resulted in rainfall amounts exceeding 150 mm in some places.

The unusually high levels of atmospheric moisture have helped fuel all these extreme rainfall events. It is a simple fact that the warmer the atmosphere, the greater amount of water vapour it can hold. You just can’t argue with this. With higher global temperatures and warmer world oceans, more water vapour will make it into the atmosphere.

Scientists who measure total precipitable water vapour in the atmosphere reported that August had the highest amount on record, and it was the 14th consecutive month with record levels of atmospheric moisture.

I know someone will ask this question: if there are record amounts of atmospheric moisture, why do we still see extreme drought, either at different locations or at different times of year?

While a warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture, it also means those higher temperatures and increased ability to hold moisture result in an atmosphere that is also very good at pulling moisture from landscapes. This leads to what climate scientists have been talking about for more than a decade.

As global temperatures increase, we will continue to see more swings from very dry conditions to very wet conditions — as if farming is not tough enough already.

Daniel Bezte is a teacher by profession with a BA in geography, specializing in climatology, from the University of Winnipeg. He operates a computerized weather station near Birds Hill Park, Man. Contact him at [email protected].

Related

About the Author